By Wesley Leak (Lincoln School of Humanities and Heritage)

Supervisor: Lynda Skipper, Henning Schulze

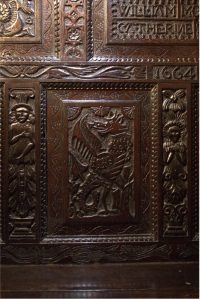

Cheltenham Museum. The settle made of oak in frame and panel construction is carved with the names of William and Catherine Mompesson with the date 1664. William Mompesson was the rector at Saint Lawrence’s Church in Eyam when the plague reached the village in 1665, where he and former rector Thomas Stanley convinced the village to isolate to stop the disease spreading in the local area. Catherine, Williams’ wife died of the plague along with 260 other villagers from September 1665 to November 1666. This relation to the plague makes Eyam a popular tourist destination today. The settle is one of Eyam Museums only objects relating to the plague. Little is known about the settle, the only information being that it was found in a second-hand shop in Chelmsford in 1954 by Cheltenham Museum. It was only at the tricentenary of the plague in 1965 that its potential significance was realised. It is said that the settle was examined by Arthur Negus, a renowned furniture expert at the time who claimed the settle was not authentic. This story is anecdotal and no evidence could be found about Arthur Negus’ assessment.

Fig 1. Mompesson Settle in situ at Eyam Museum

This research project aims to understand the settle in more depth to assess its authenticity and provide more information to the public through the museum. Collaborating with Eyam Museum’s curator Owen Roberts three key questions were set:

-

-

- How old is the settle – was it a contemporary piece made for the Mompesson family, or could it be a later commemorative piece?

- What do the carved symbols on the settle mean?

- How can visitor understanding of this piece be improved?

-

These questions would be answered through looking into the carvings and the manufacturing techniques evident on the settle. The first step of my research was to visit Eyam Museum to see the settle and take a detailed look at it supervised by Lynda Skipper and Henning Schulze, both lecturers in the conservation department. We documented it with photographs and measurements. Henning, an experienced furniture conservator helped identify manufacturing marks and techniques on the settle. We initially concluded that the settle back and chest are different through their making technique and manufacturing marks, and that the settle had been altered in the past.

Fig 2. Photographing the Settle in the Museum. Restricted space made it tricky.

In response to these key questions a report on the settle was produced for Eyam Museum, looking in great depth at different aspects of the settle. This information will then be used to improve display information for visitor understanding of the settle.

A summary of the findings of manufacture of the settle.

Overall, the seat part of the settle has the more original older features than the back rest. The seat section has definite marks of hand resawing and planing but this section has been altered through the cutting short of the legs which required new wooden nails and resulted in missing pieces. It is conceivable that the back rest was added to the seat later to make the settle as it appears today, for example by adding to a panelled chest. This would explain why various sections appear to have been taken apart in the past and secured with new wooden nails on re-assembly. The cutting short of the legs is likely a separate earlier alteration due to the settle being used in a damp place encouraging rot and insect infestation. Overall, the structure may contain older and newer parts and the settle has been taken apart at some stage. The repairs largely are of good quality, it is, however, difficult to tell when these may have been done. It is possible that they were done in preparation for sale in the antiques

Fig 3. Example of the edited leg on the Settle.

Fig 4. Panels with Mompessons names (right), Serpents (left) and Wyverns (Central) visible. along with grape vines and 17th century style carvings including branching trails above and below the central panel on the image.

Carvings Summary

In summary, some of the carvings do have meanings that relate to the plague and could have been meant in this way. At the same time, they can be inferred differently possibly relating to Mompesson’s Christian beliefs and his family, including their newly born child in 1664. The presence of the St Andrews cross could link to the name his church at Eakring where he was a popular and long serving rector after his time at and could have been made for Mompesson or to commemorate him and his former wife Catherine in Eakring. The carving style matches that of the 17th Century and it could simply be that the carvings were made to the fashion of the times. More in depth but earlier analysis of the carvings on the settle can be found in my history and heritage blog here: https://history.lincoln.ac.uk/2022/07/29/a-uros-conservation-project-the-carvings-of-the-mompesson-settle/

Conclusion

Overall, a lot has been learnt about the settle, but a definite answer to its authenticity still cannot be found. However, this research has brought up possibilities of the reasoning for the settle and how it is today. Opinions can be formed from reading the evidence gathered which are likely to differ from person to person. Nonetheless this is certainly a very interesting settle whether contemporarily or commemoratively linked to William and Catherine Mompesson.

*To view the research poster for this project, please click on the thumbnail below: